The economic evolution of Aberdeen: A case study; The extent branch plant inward investment effectuated a multidisciplinary industry integrated economy characterized by longevity

The economic evolution of Aberdeen: A case study; Critical evaluation of the extent branch plant inward investment effectuated a multidisciplinary industry integrated economy characterized by longevity centered on the offshore oil industry in Aberdeen1970-2020.

Introduction

The branch plant inward investment paradigm in a Scots context can be linked to the 1945 distribution of industry Act. Through data gathered on employment and investment it was clear Scotland was a distinct economic area of the UK (United Kingdom). The act was enacted at a time when there was a realization Scotland had to change her economic structure and modernize moving away from the resource dependent industries to a more flexible mobile modern industry strategy (Tomlinson and Gibbs 2016, p. 590). The first phase of deindustrialization began between the 1950s- 1960s and restructuring the Scots economy became a priority (Phillips, 2013, p. 99). This case study will be structured in 3 areas, initially describing the features and associated concerns of the Branch plant, secondly analyzing the features and concerns of the Branch plant, and latterly summarizing the findings.

Description and concerns relative to the Branch plant

Branch plants are subunits of diverse or multi-plant corporations and would become a prominent feature of restructuring industry in Scotland. Initially this form of inward investment was welcomed and latterly seen with skepticism, concerning the notion on the one hand of a Scots economy and additionally criticism of branch plant characteristics and the peripheral nature of factories designed for assembly only and detached from primary activities of the companies. Further, it was noted Scotland would lose out on research and Development (R&D) opportunities and be exposed regarding decisions by corporate headquarters (HQ’s) based abroad (Tomlinson and Gibbs 2016, p. 590). Moreover, additional concerns of the negative effects of branch plants were for example lack of stable jobs and low wages, restricted localized backward linkages, corporate or local, acquiring government subsidies, and lack of multiplier effects (Sonn and lee, 2012, pp. 1-2), alongside predictions of short-term boom followed by longer-term decline. It is a commonly accepted tradition in social science critical analysis of the branch plant, that it is robustly critical of the external control employed on regional economic development (Hymer, 1972; Firn, 1975; Massey, 1984; Turok, 1993 cited in Cumbers and Martin, 2000, p. 32). Particularly relating to the association with a deskilling nature of low wage assembly line work and where the replacement of traditional industry takes place, this effect then facilitates the disintegration of work locally. Additionally branch plants are viewed as being disconnected from their localities via external control and therefore loosely integrated with limited embedding in local regions. It can be argued these features do not provide outward local economic development in the long-term (Cumbers, 1998 Cumbers and Martin, 2001, p.33). This case study will examine these concerns and analyze to what extent they applied to Aberdeen's experience immersed in the international oil industry.

Analysis

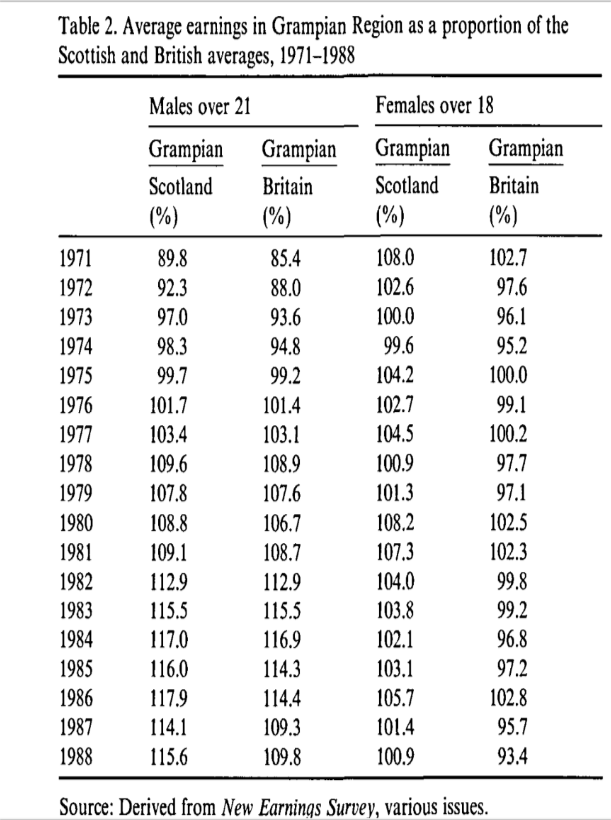

The North Sea oil discovery in the mid 20th century brought huge benefits to the city of Aberdeen alongside huge inward investment. The oil boom attracted 200 new companies and with them 1000s of new residents, this in turn drew investment for new housing, schools, and offices (Britannica 2022). The Oil industry brought about the transformation of Aberdeen's stagnant economy, with new employment in well paid jobs created a flourishing and dynamic atmosphere in the city. The new prosperity caused rapid population growth and reversed Emigration (Harris et al., 1988 cited in Lloyd and Newlands, 1990, p. 32). As shown in table 1 by Lloyd and Newlands (1990), there is consistent growth in employment in the oil industry between 1973 and 1988. The table only accounts for residents within the Grampian region, offshore and onshore, the official figures are higher, although consider workers from outside the region. The consistent increase tapered off in the mid 80s due to a worldwide drop in oil prices, within a six-month period between 1985-86 oil prices per barrel dropped from thirty dollars to ten dollars. There was a significant drop in employment in that period as indicated again in table 1 by Lloyd and Newlands (1990) of 4100 between1985-86 then a further drop of 6200 between 1986-87. The oil industry employment multiplier effect, meaning the amplification of employment by formation of new localized businesses within the region were estimated at 1.78 in 1981 (Harris et al 1987 cited in Lloyd and Newlands 1990). With every hundred jobs in the oil sector the multiplier effect created a further seventy-eight jobs in local business e.g., restaurant, pubs etc. After 1981 the oil sector seen a rapid growth and by 1985 it is estimated if calculated by the 1.78 multiplier, although certain factors had changed, then the number of oil dependent jobs would be 68,000. These figures indicate 40% of Aberdeen's workforce relied on oil generated income (Lloyd and Newlands 1990, p. 32). Initially wages for men in the oil sector were significantly lower than the national average, however, by the 1980s climbed to 15% higher than the average earnings as shown in table 2 below by Lloyd and Newlands (1990). Women’s earnings were more ambiguous with no obvious signs of improvement as was the case for men working outwith the oil sector (Mackay and Moir, 1980 cited in Lloyd and Newlands,1990, p. 34).

Source; Lloyd and Newlands (1990)

source; Lloyd and Newlands (1990)

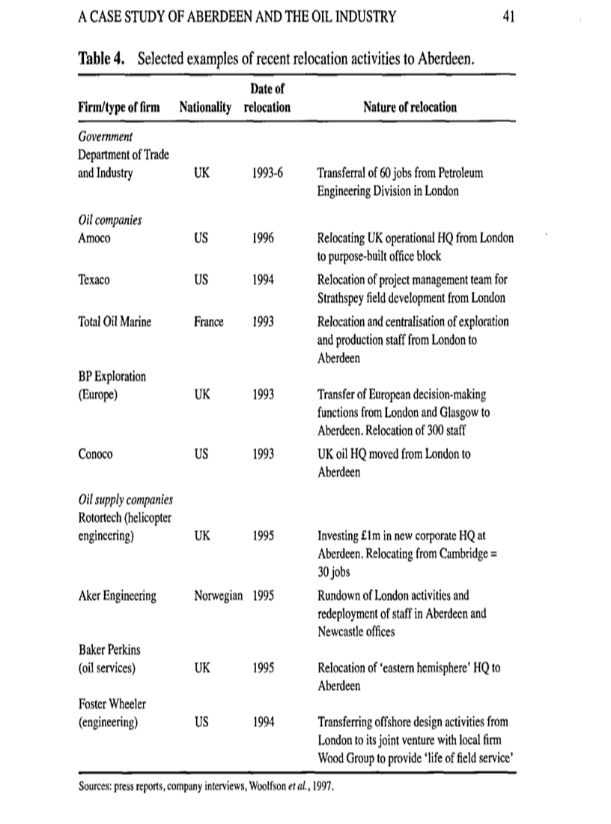

After 1985 there was significant restructuring in the oil industry in terms of downsizing through cutting jobs and corporate structure processes of rationalizing bureaucracies with a refocus on central oil and gas enterprises. Post 1987 the relationship and structures were streamlined due to a drop in oil prices and greater increases in costs. This involved deeper integration of contracts and where management and risk were centralized, via a single contractor, allowed concentrated relationships to be strengthened (Cumbers and Martin 2001, p. 37). TNCs headquartered outwith Scotland dominate oil development in Aberdeen. Local businesses have had limited success breaking into the more technically refined aspects of the oil industry, for example engineering and drilling services, due to embedded relationships with foreign contractors and suppliers by the domination of corporate entities (Cairns and Harris, 1988 cited in Cumbers 2000, p. 374). In 1993 the DTI was relocated to Aberdeen after which 5 major oil conglomerates relocated to the city with management and operations indicating a more permanent base. This in turn had the effect of differential arms of the oil industry, e.g., suppliers and contractors following suit. The consolidation period tapered off by 1996 as indicated in Table 4; however there has been no backward slide since by oil companies or contractors (Cumbers and Martin 2001, p. 40).

source; Cumbers and Martin (2001)

In terms of backward linkages, meaning outward enterprises that create localized formation of additional forms of revenue and economic value, it is pertinent to note that the bulk of specialist equipment, materials and products are sourced outwith the region and the UK. Therefore, Aberdeen's oil structured eco system is one of limited but substantial peripheral material linkages. Focused research in Aberdeen is minimal in R&D and predominantly taking place in England concerning the central technologies, although Aberdeen does play a limited role in innovation. In the periphery of the oil supply ecosystem of Scotland and UK there is substantial indigenous company integration making up around half of engineering companies. However, these firms as indicated in the table below by Cairns and Harris, (1988) are comparatively small in terms of employment encompassing a mere 16% in engineering, a core field locally and 9% in Scotland, respectively. Whereas North American firms employ 75%. Scotland and Aberdeen’s participation is primarily on the periphery of the oil production ecosystem as shown in the table by (Cairns and Harris, 1988, p. 501).

source; Cairns and Harris, (1988).

By 2014 North Sea oil experienced a 40% fall in production levels equivalent to those of the 1970s. Government concern prompted the Wood review; later that year the proposals were accepted, and an extensive oil investment and infrastructure plan was implemented (GOV.UK, 2022). The UK subsidized the offshore oil and gas industry with an annual average of £9billion (Bast, et al. 2015), 2014-2015 and a further £13.6 billion between 2016 –2020 (Ethical, 2022). It is hard to estimate the extent of total funding via tax incentives and subsidies as the figures are split in complex ways between State-Owned Enterprises, the private sector and third sector.

Conclusion

In summary Branch plant inward investment by all accounts in Aberdeen can be viewed as an example of economic success. The offshore oil industry has become an important feature to the Scots economy and energy strategy. Although for differential industries branch plants have been viewed as abject failures, hence the Branch Plant Syndrome label. The realization Scotland must plan for a new future once again is a priority with new pressures of net zero and a deeply interconnected global economy. Aberdeen's Offshore industry has afforded the region extensive knowledge, learning and innovation. The technologies that have been developed and used in the North Sea have become exportable with local firms benefitting from new markets. Additionally, there is evidence that the oil sector has had the foresight to invest in decarbonization and renewables. Aberdeen's Renewable Energy Group, (AREG) set up in 2003, has invested £5, billion in low carbon Infrastructure projects in the Northeast with the skills, technologies and expertise of oil energy producers and specialist services from the sector (AREG, 2022). Interindustry connections and trust have been fortified by the continuity of the oil industry in Aberdeen. In terms of longevity the Branch plant has contributed to the success and robustness of the industry. During the last 5 decades there have been periods of limited capital flight, for example during the mid 1980s and 2008 although not to the extent that this manifested in crisis. Wages for oil sector workers have remained higher than the national average with some estimates at 21% higher. While unemployment within the region has settled at just above 2% (Aberdeen Prime Four, 2022). Innovation within an industry depends on long term relationships, a feature of the Offshore oil industry in Aberdeen that has allowed it to become known as the Oil capital of Europe. Local companies that flourished in the competitive atmosphere of Aberdeen's early offshore oil discoveries have benefited from the massive inward investment and experience of the outward influence of the Branch plant by integration and sharing of technology and knowledge with local companies. The local companies that managed to penetrate the industry in the early years gaining extensive expertise and knowledge working in the extremely inhospitable environment of the North Sea, are now able to sell this expertise and knowledge abroad in subsea oil exploration. The long-term integrated industry relationships that have formed have in turn allowed Aberdeen to innovate in expectation of oil reserves being more difficult to find and extract, with pre-emptive extensive subsea extraction R&D currently in progress. Technological expertise and specializations have become a valuable commodity in moving into other energy domains. Aberdeen is looking to the future and has evolved beyond a branch plant economy, branch plants helped to embed an integrated economy that has facilitated longevity. Current oil reserves are estimated at 24bn barrels of oil, approximately 3 decades in terms of an extraction period from the North Sea (People with Energy 2018). The question now is, will Aberdeen make a smooth transition and success in alternate domains of energy and net zero ambitions?

Hey if you enjoyed the read, consider giving a tip here:

References

Aberdeen Prime Four (2022), Aberdeen's Prime Four,AberdeenPrime Four [Accessed 10th November 2022]

Areg, (2022) Aberdeen's Renewable Group,Aberdeen Renewable Energy Group | Developing the Renewables Industry (aberdeenrenewables.com) [Accessed November 1, 2022]

Bast, E., Doukas, A., Pickard, S., Van Der Burg, L. and Whitley, S., (2015). Empty promises: G20 subsidies to oil, gas and coal production.

Britannica (2022) History, Facts, Oil, Industry, Britannica,Aberdeen | History, Facts, Oil Industry | Britannica [Accessed October 29, 2022]

Cairns, J.A., and Harris, H.A., (1988). Firm location and differential barriers to entry in the offshore oil supply industry. Regional Studies, 22(6), pp.499-506.

Cumbers, A., (2000). Globalization, local economic development, and the branch plant region: The case of the Aberdeen oil complex. Regional Studies, 34(4), pp.371-382.

Cumbers, A. and Martin, S., (2001). Changing relationships between multinational companies and their host regions? A case study of Aberdeen and the international oil industry. Scottish Geographical Journal, 117(1), pp.31-48.

GOV.UK, (2022), Wood review Implementation, Wood Review Implementation - GOV.UK (www.gov.uk) [Accessed Nov 1, 2022]

Jim Tomlinson & Ewan Gibbs (2016) Planning the new industrial nation: Scotland 1931 to 1979, Contemporary British History, 30:4, 584-606

Ethical, (2022) Fossil fuel subsidies in the UK,Paid to pollute: fossil fuel subsidies in the UK and what you need to know | Ethical Consumer [Accessed 1 November 2022]

Lloyd, G. and Newlands, D., (1990). The interaction of housing and labour markets: an Aberdeen case study. Land Development Studies, 7(1), pp.31-40.

People with Energy (2018), How much oil is left in the North Sea, How Much Oil is Left in the North Sea? (peoplewithenergy.co.uk) [Accessed 10th of November 2018]

Phillips, J., (2013). Deindustrialization and the Moral Economy of the Scottish Coalfields, 1947 to 1991. International Labor and Working-Class History, 84, pp.99-115.

Sonn, J.W. and Lee, D., (2012). Revisiting the branch plant syndrome: Review of literature on foreign direct investment and regional development in Western advanced economies. International Journal of Urban Sciences, 16(3), pp.243-259.