Introduction

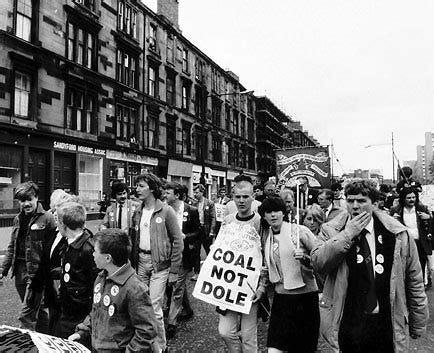

The premiership of Margaret Thatcher 1979-1990 was a landmark period in Britain’s political history with the beginnings of the neoliberal order and a neoliberal political economy embraced by Margaret Thatcher and Ronald Reagan of the USA among the vanguard. This period in Britain was punctuated by the war in the Falklands, the war on trade unions, political attacks on the working class, race riots in London, Birmingham, and Liverpool, the poll tax riots, trade union strikes, mass unemployment, and social upheaval. This essay will initially explore the events processes and strategies that were employed in the political war against trade union power and the working class during the Thatcher premiership from 1979-1990 and how this impacted Scottish communities. The events that unfolded during this era were inordinate and exceptional in British history. The coal miners’ strike being the catalyst and final battlefield where ideological supremacy was to be tested. Margaret Thatcher initiated an accelerated pace of deindustrialisation and implemented a variety of reforms during this period that can be viewed as being neoliberal in character, although, branded in her unique format. The primary thread relating to this essay is how deindustrialization intersects with the Thatcher premiership neoliberal policies of the period and how this manifested in Scottish industrial communities and wider society. Deindustrialisation resides at the core of modern British history, with many British studies having forwarded productive debates on the topic. The Thatcher premiership played a significant role as a forerunner in the establishment of the neoliberal order. This essay concludes with observations that the Thatcher premiership's rapid deindustrialisation accompanied by neoliberal policies impacted Scottish industrial communities in myriad ways that manifested predominantly in the negative, with high unemployment, rising crime, rising divorce rates, ill health, substance abuse, decimated work, and community identities, democratic disconnect, inordinate rise in mental health difficulties and hyper-individualism expressed in societal anomie, reducing social solidarity.

Pre-eventual conditions and events influencing a political attack on Trade unions and the working class.

During the Heath government 1970-1974, the Conservative party was perceived to have been repeatedly humiliated by trade unions, initially in 1971 by the Upper Clyde Shipbuilders (UCS) led by stewards Jimmy Airlie and Jimmy Reid 1971, members of the Amalgamated Engineering Union (AEU) and later by the miners’ strikes of 1972 and 1974, with the National Union of Mineworkers (NUM) defeating the government. This was to leave a lasting bitter legacy in the Conservative Party which was to inform Conservative industrial relations reaching into the 1980s and the Thatcher Premiership resolve never again to be beaten by trade unions. During the Thatcher premiership 1979-1990, Scotland was impacted to a far greater extent than England in the accelerated final phase of deindustrialisation, with the initial process beginning in the late 1950s. Scholars for example, (Collins and McCartney, 2011) and (Tomlinson 2021) describe this process as a characteristic of a neoliberal political attack on the working class and trade unions of Britain. Scotland was more vulnerable than the rest of the UK, due to her reliance on heavy industry for employment. As Clarke (2023) articulates, there was a tsunami of closures resulting in high unemployment, poverty, and deprivation, increasing in communities where industrial production dominated. For example, in Greenock a town reliant on shipbuilding, sugar refining, and textiles, where there were forty-three unemployed people per job advertised in 1986. Deindustrialisation, therefore, predated Thatcherism. Following the 1979 election of the Thatcher government was a new distinct but accelerated phase in deindustrialisation political management. In consequence, two million jobs in the industrial sector across the UK were lost in the four years leading to 1983 with central and the west of Scotland being overwhelmingly affected.

Thatcher's brand of Neoliberal policy

The working class and their communities were predominantly affected by deindustrialisation which resulted in high unemployment, poor health, and increased crime and substance abuse, during and continued after the period 1979-1990.

Collins and McCartney, (2011) suggest, that there is little disagreement, that post-1979 the Thatcher Premiership embarked on a continuous attack on the working class and deindustrialisation was a prominent feature. Furthermore, there is the widely accepted view of a neoliberal attack and the (Scottish effect), that deindustrialisation bore on Scotland, and was political to a greater extent than elsewhere in Europe undergoing the same processes during the same period with wider consequences and less mitigated for Scotland. The Index of Economic Freedom and the Luxembourg Income study provides evidence that the UK’s policy course differed from comparative European nations during this era. The Glasgow Centre for Population Health’s, study on deindustrialisation, concurred with these findings, suggesting a more robust neoliberal agenda, not only departing by conception but by its effects in Scotland. Thatcherite policies are characterised by the privatisation of nationalised industries, for instance, steel, coal, gas, telecommunications, and other utilities, while reducing regulations on businesses in finance and labour. Additionally, deindustrialisation was responsible for the loss of heavy industry and manufacturing jobs. During the 1980s, the West of Scotland in particular, was subject to the devastating impact of deindustrialisation, more so, than most areas throughout Britain, which Jim Philips indicates, was a failure of government policy to manage manufacturing closures. In terms of monetarism, government policy was to control inflation by limiting the money supply which then resulted in high interest rates. Furthermore, limiting taxation on businesses and those on high-scale incomes to stimulate growth, was largely unsuccessful, with limited evidence of effectiveness. While weakening the power of trade unions and lowering wages. Trade-union influence was emasculated via targeted employment and industrial relations legislation.

Tomlinson, (2016) suggests, that British deindustrialisation should not be viewed as declinist, but the focus is better placed on how the processes of deindustrialisation, reformed the labour market and therefore, employment in the UK. Furthermore, raising questions as to the profound implications for government policy and the ways this impacts social inequity and family incomes. For the working class, the social implications were employment insecurity and in many cases deprivation, which continues into the contemporary period, where the half-life of deindustrialisation is still toxifying communities, their identities, and their urban environments. The language of declinism was employed to rationalise the justification of redistribution of wealth from the poor to the rich. Lawson (2020) in examining the ruins of deindustrialisation in Scotland, contemplates, how middle-class urban explorers may be captivated by the forbidden nature of industrial ruins and their aesthetic, beautified in the abstract, although, isolated from the social context they were formed, these ruins are equally a symbol, one of uniting displaced workers and memory, immersed in anger and grief. This latter sentiment is born out in the lived experiences explored by McIvor (2019) and his use of oral history, exploring the meaning of job loss and ways deindustrialisation has eroded the hard-won post-war positive effects on social well-being and health of men in Glasgow, viewing deindustrialisation as a form of trauma on working-class bodies, while impacting identity, masculinity, and memory.

Mining trade unions' response to Deindustrialization and neoliberalism

The ruling class and their representatives have viewed trade unions as their primary threat, unlike the (Labour Party), trade unions and organised labour power have always troubled the ruling groups. During the latter half of the 1970s solutions on what could be done to limit labour power and trade union influence were discussed in detail. In the case of the coal miners, this was to take precedence, taking note of their industrial power in the 1970s, showed that the political attack must be calculated and strategic. For Margaret Thatcher state-owned subsidised industries and British firms were a source of frustration, and in her view on nationalisation, was one that maintained a constrained investment for private companies, with the result of capital being invested abroad. Her views on the post-war consensus and that nationalisation and regional planning were to be curtailed, however, her widest concern was the growth of trade union power. The belief was trade union wage demands, impacted inflation negatively, and would hamper her goal of low inflation. Additionally, her avid belief in parliamentary sovereignty was the driver that ejected the corporatism consensus, which permitted trade unions to influence government decisions. The Stepping Stone programme was to link the public perception of trade unions with socialism and the Labour Party in justification that legislation should be equated with a rejection of socialism and change the role of Trade unions. This was a false equivalence as trade unions are intrinsically capitalist objectively, while socialist subjectively. When the report was leaked in 1978 to the Economist, the Conservatives proffered a denial, this strategy, was not party policy.

State motives and strategy (2)

Saville (1985) states, that anti-union legislation in concert with rapidly increased unemployment would neutralise the trade union movement, implying that the Conservative government were purposely and strategically causing high unemployment to reduce the power of trade unions. In the case of the miners, were identified for special consideration, perhaps considering the industrial power and the political ramifications this may entail, as the perceived humiliation of 1974 gives evidence to. The 1980 Employment Act was one aspect of the Conservative party strategy; legislation constructed with the specific intention to significantly weaken unions and in particular the coal miners, in expectation of the war to come. The 1980 Employment Act banned secondary picketing and strikes, restricted unfair dismissal, and maternity rights, and made closed shops much harder to maintain. Furthermore, limited picketing numbers and required votes for new closed shops. Later, after the re-election in 1983, the Thatcher government introduced further legislation, the 1984 Employment Act, targeting union influence on Labour and industrial action. The focus of this act, resulted, in an assault on the internal organisation of trade unions, and their relationship with the Labour Party. The Employment Act of 1984 mandated secret ballots for union leadership, strike votes, and limited political fund use, aiming to weaken the Labour Party’s finances and make strikes more difficult to finance. During the period 1980-1984, coal stocks were increased as a strategy in preparation and anticipation of a strike by the coal miners. The police were employed to break up pickets and limit the effectiveness of the strike. In addition, the intelligence services were deployed in surveillance of the NUM leadership.

Reaction to political attack

The Scottish Trade Union Congress, (STUC) while being the anti-trade union legislation's most outspoken critic, failed to affect the implementation of the Employment Acts of 1980 and 1982, which removed legal protection for strikes in support of other trade unions and secondary types of Industrial action and then again by further attack via the Employment Act 1984. As a result of the new employment legislation criteria, in the period January 1982 - March 1983 resulted in the loss of 3 national ballots by the NUM, concerning pit closures and pay claims. After the 1983 June General election Margaret Thatcher appointed Ian McGregor to head the NCB, taking up his post at the beginning of September 1983. This was expressed with disappointment by the NUM; McGregor immediately declared uneconomic collieries would be closed. The NUM reacted by calling for an overtime ban on all workers in October linked to the closure of pits, this caused difficulties and disputes in Scotland and Yorkshire. During the period 1980-1984, the Labour Party in opposition failed to forward economic arguments against closures and failed to highlight dubious accounting methods employed by the NCB, which would have enabled opposition to the government's justification for the NCB to close uneconomic pits. Later those accounting methods were shown by academics to be wrought with flaws. In Scotland the NCB’s aggressively anti-union policy after the closure of the Kinneil pit in April 1983, was driven by Albert Wheeler chairman of the Scottish Coal Board, rotating his managers from colliery to colliery with the aim of short-term economic performance. In this context was the continual provocation by managers and heightened workplace conflict, resulting in trust erosion between the NUM, miners, and the NCB.

The sequence of events leading to the 1984 strike began on 1st March 1983, Cortonwood pit was marked for closure and a week later the NCB informed the NUM there would be a four million tonne cut in production 750,000 tonnes of Scotland's 5.9 million tonne capacity in 1984-5, part of McGregor’s rationalisation plan. The miners' strike began with the announcement of the closure of the Cortonwood mine in South Yorkshire. The NUM called for area strikes in Yorkshire and Scotland, hoping for a domino effect that would lead to a national strike. Their strategy also relied on solidarity from other unions and political support from the Labour Party. However, the strike did not unfold as planned. There was discord within the NUM, with some miners continuing to work. Additionally, other unions and the Labour Party did not provide the expected level of support. Controversy over Arthur Scargill leader of the NUM not calling a national ballot contributed to the controversy of the strike allowing the Conservatives to argue the strike was undemocratic and with the employment of flying pickets leading to police clashes and further undermining the strategy, drawing media attention away from the economic argument against closures and focusing on the violent clashes with police. Furthermore, the steelworkers, dockers and railway workers were not willing to unite in solidarity with the miners as their jobs were under threat due to deindustrialisation and the now limited trade union power via Industrial relations and employment law. Moreover, Arthur Scargill’s calling for financial aid from the Russian and Libyan governments further alienated many who supported the miners in their cause, considering the 1980 Libyan Embassy siege where a young WPC was murdered and was still at the forefront of public memory. In addition, the flawed strategy to call a strike in March when energy use was lower added to a long-protracted strike causing hardship to miners’ families. The strike would have had a far greater impact if called at the beginning of Winter, in the UK this would be around mid-September when temperatures are known to drop considerably and require higher energy usage.

Mining Community support networks and solidarity 1984-1985

Community support networks and social solidarity formations within communities were to be a significant support base, emphasising how miners garnered support and from whom this support came. The miners were able to muster support not only from their community but from wider society and groups who may not immediately be considered as obvious allies, in that they did not have a direct relationship with mining communities.

Geography was a central part in detailing the support of miners during the 1984-1985 strike, many groups who organised and ran those support organisations were directly linked by social identification and based within the community of the miners, for example, by wives, girlfriends’ mothers and daughters, local businesses, and retired members of the community. Others, however, were external to the coal mining communities they supported and, although they did not have a direct identity relationship with the miner’s communities identified with their cause. The protection of employment security and way of life were dominating factors and in this context were drivers of the miners’ strike. Collective action was bolstered by class, occupational, and community solidarity and social cohesion, informed by Coalfield work history, tradition, work and political culture, identity, reciprocation, and altruism, that not only emerged within those communities but was evident, although, in a more diluted but significant sense in wider society. The location of a support group impacted its form, goals, and operation. Groups within coalfields often had direct ties to strikers and were frequently organized by miners' families.

The National Union of Miners Scottish Area (NUMSA) provided material and financial resources to the miners via trade unions and some elements within the labour party, for example, Dennis Canavan, the Falkirk West Labour MP, Martin O'Neill, Labour MP for Clackmannan and Harry Ewing, Labour MP for the Falkirk East constituency. This support and resources were accompanied by a plethora of organisations and individuals, in which, local area groups played a vital role in furnishing the type of assistance that was a core factor in maintaining the longevity of the strike. These diverse groups, ranging from miners' wives to students, focused on accommodating strikers and supporters from outside their local areas, fundraising and maintaining morale. Women in Scotland’s mining communities played a crucial role in maintaining the miners’ strike of 1984-1985. Mick McGahey writing in April 1984 explained women were extremely effective political advocates in both the media and at public rallies. Philips, (2017) suggests, that it was a daily hot meal and weekly grocery bags that were crucial, particularly to single miners, and it was in the multi-arena of local area centres, the ‘soup kitchens’ and welfare clubs, that women cemented the strike, combining material and moral fortitude. In addition, women bolstered the resolve of men in the strike by affording a social cost in the rejection of men who broke the strike, using emasculating gendered language, for example, ‘not real men’, and other more colourful terms, this was particularly strong in Fife and Midlothian where women actively participated in the strike.

Types of Solidarity Interlinks

Scotland stayed more united during the strike, more so than England, the Scottish trade unions benefited from strong solidarity by miners who never wavered. The shared past of Scottish union leaders Milne and McGahey as members of the Communist Party of Great Britain, fostered a strong working relationship that was not replicated in England. Solidarity was emphasised in the narrative of mining communities during the miners’ strike and intrinsic as a part of the rhetorical strategy for collective action, highlighting the cohesion in localities of the Scottish coalfields during the 1980s. During the 1984-1985 period, activist literature placed the cementing nature of communities as the lintel of the resolve shown during the strike. By the end of the year-long strike, fifteen thousand miners, more than half of Scotland’s coalfield workers had stood united in their struggle to save their industry. Furthermore, class solidarity was a factor that coalesced alongside occupational and community solidarity galvanised by social democratic rhetoric and support shown by the sympathetic Scottish media. Trade union solidarity was limited during this period from the industrial sector and manufacturing trade unions, many unions had as the government anticipated retreated to survival mode for their organisations, under the legislative conditions pre-empted by the Stepping Stones plan.

Pat Egan a NUM activist indicated Jimmy Reid’s criticism of Arthur Scargill, using his exposure as a newspaper columnist, made the effort to create alliances across trade unions more complicated, this was one of the many examples that limited the mining trade unions bolstering of solidarity for the miners and their communities with other trade unions. Despite the challenges, women's groups emerged as a powerful force, mobilizing significant portions of the community and forging connections with union branches across various sectors. Their actions showcased the potential for solidarity beyond traditional union structures. Mining communities during the strike were directed by the social and cultural traditions and their shared class-based experiences, alongside the values developed from the former, combined with cultivated networks, conditioned their collective behaviour with intense solidarity.

Discussion

Neoliberalism's intersection with Deindustrialisation and the moral economy

The processes of deindustrialisation began in the early 1950s and were initiated decades before the Thatcher Premiership of 1979-1990. Scotland's industrial struggles after World War II, post-1945, were not effectively addressed by either the UK or Scottish representatives.

This left Scotland especially vulnerable to the economic hardships and Conservative policies of the 1980s. Early deindustrialisation processes and form, beginning in the 1950s were much slower and were more mitigated by balancing deindustrialisation with the need to maintain relatively low levels of unemployment, until the 1970s, when levels of unemployment were beginning to increase. By the 1960s there was a strong signal the coal industry and many other industrial sectors were changing, turning coal miners’ communities into the industrial Nomads of Britain, shipped from pillar to post in search of employment. The moral economy was an argument that asserted, that job losses in one sector should be mitigated by the creation of further jobs in alternate sectors or transference of the unemployed within the same sector to more efficient subunits within their industry, for example, in the coal industry pit closures and job losses were met by several criteria; namely, coalfield closures would be negotiated and secured with workers, while emphasising economic equilibrium with individuals, their families and communities. Unemployment was mitigated by a transfer of those unemployed or redundant to pits with increased production or to alternate sectors. The fear by miners and their unions in 1984 was elevated by erosion of trust in the NCB and their projected pit closures, where the miners distrusted the projections; the fear was not that they may have to move to find work, but that there would be no coal industry at all. Alan Stewart, Minister for Education, praised those miners of the 1984-1985 strike, who continued to work, stating, that by returning to work they were defending the future of Industry in Scotland. In the aftermath of the strike of 1984-1985 with hindsight and was previously articulated, this statement would later prove to be wildly inaccurate, with the industry going into a steep incline after the miners’ strike, as did other industrial sectors, for example, Ravenscraig steel works in Motherwell closed in 1992 and with the last coal pit Longannet closing in 2002.

Perhaps in consideration of the moral economy argument this was in part a factor responsible for the great upheaval during the Thatcher premiership as miners’ expectations were blunted, particularly in Scotland where the criteria were equated with, as Philips, (2020) suggests, communal attitudes to the economics of coal extraction being heightened, dyadic with the social values of the moral economy. The moral economy in essence aligned with the post-war social contract and the Beveridgean social settlement, a feature of which was to be employed as an argument by Thatcher suggesting workers had forgone their side of the bargain, the opposing argument inferred by workers, was that the state was in breach of their end of the contract. A quote from the Beveridge report states, “The state should assume responsibility for preventing mass unemployment” (Wolman, 1943, p. 5). By all accounts in the documents analysed this criterion was ignored or was unworkable, possibly, due to a lack of investment in new equipment and technology by Britain’s corporatist leaders in the early years of deindustrialisation, and neglect in addressing the industrial vulnerability of Scotland, when there was a realisation of a global shift in economic dominance and a lack of vision to pre-empt future unemployment. This can be further extrapolated as a cynical non-caring attitude towards the peasants by capital, manifesting in plutocratic revanchism.

Strategies

The Thatcher premiership abandoned the principles of the moral economy arguments of the Scottish workers and set in motion a Conservative party-led strategy that was developed in the late 1970s with a variety of external groups, for example, the Economic League, Common Cause, the Freedom Association, the Selsdon group and the Confederation of British Industry, among many other groups representing capital; that was to initiate an accelerated form of deindustrialisation and with the aim to limit trade union power. The implementation of the stepping stones plan set in motion events in the preparation and formation of a strategy that would manifest as a political attack. It is pertinent to add, that the political attack and war on workers initiated during the Thatcher Premiership was not merely driven by economic concerns, but the government narratives were laden with ideological dogma as was the response by trade unions driven to some extent by ideology, free market capitalism versus socialism. In addition, there is some cause to represent the attack as a punishment on the working class and trade unions, due to the perceived humiliations sustained during the 1970-1974 Heath government, where the purpose was not humiliation, but merely workers protecting pay, working conditions and their way of life.

The impact of Thatcher’s strategy to accelerate deindustrialisation and limit trade union power in Britain was keenly felt in all heavy industry-based communities that came under attack by the state, particularly in Scotland with her reliance on heavy industry. The miners’ strike of 1984-1985 was anticipated as the inflexion point that confirmed the dominance of the Thatcher government. In avoidance in 1980 of a standoff with the NUM, this was a tactical retreat, and in the intermediate, while the groundwork was being prepared for the anticipated battle with the working class and their trade unions, while coal stocks were increased to limit energy impacts of a future strike, and in the interim, legislation was being constructed employing the welfare state, in the minimisation of workers benefits, alongside stipulations that would diminish the effectiveness of trade unions, and affording the police extra powers. Considering the preparation, strategical processes, and the considerable resources employed by the Thatcher government and the detailed circumstances leading to the miner’s strike, the interpretation then suggests actions by the state declaring war on a large contingent of her population, a paradoxical injustice paid in part, by the victims. It was a free-market/neoliberal ideological attack on the working class, carried out by ideological fanatics who cared not for the carnage they were initiating against the working class.

The Trade union movement was slow to react and missed vital opportunities to present arguments in opposition to the economic arguments of the Thatcher government. The National Coal Board (NCB) used faulty accounting practices to justify pit closures. An analysis of their reports showed these closures would not save money, and the true financial picture of the coal industry was much better than presented. The Labour Party and the National Union of Mineworkers (NUM) failed to effectively expose these accounting errors to the public. Additionally, disunity flourished by initiating clause 41 which was a reaction to the ballot losses of the previous two years, in large part due to employment legislation and in effect was used to supersede a national ballot, which was a constitutional norm of the NUM, and proved to be a fatal error in judgement, negatively impacting the unity of the miners and their trade union and would play a miner but significant part in their eventual defeat. In terms of ammunition, Arthur Scargill’s strategy of climbing over the NUM constitution, approved by the NEC on March 8, provided dual weapons with which the government could employ against the miners, namely, that the strike was illegitimate and undemocratic and was used to the full extent via the media.

Rationalisation for miners in the context of the strike of 1984-1985

On the miner’s part rationalising the immediate impact of loss of earnings and impact on their families was weighed with the immediate social costs that would be felt by community rejection. Equally for those on strike, wage loss concerns, and family impact were weighed against the possibility that in the long term, their industry may be decimated. Short-term rationalisation choices against long-term effects were both calculated, and decisions were made based on what was prioritised in the process. In Scotland, most miners remained on strike for the largest part of the strike, unlike in England where many more miners returned in the early months of the strike, whereas in Scotland the strikers remained cohesive until the final months leading up to the end of the strike. The miners in Scotland predominantly accepted a financial loss, in immediate wages as the price to be paid for securing a long-term future, by employing the customs and values situated in the moral economy and raising the social costs of returning to work and strike breaking. Leading up to the early months of 1985, only a very small minority of strikers were prepared to incur this cost. In juxtaposition strikebreakers can be viewed as irrational, adopting short-term gratification for long-term inutility, although, in the short term they benefitted from wages, however, in helping to break the strike, reduced long-term employment and total earning capacity in the coalfields, greatly reduced by an accelerated closure of collieries, although, many were granted substantial redundancy payments in the period after the strike. However, incurred a high social cost by the rejection and stigmatisation from their communities that lasted well beyond the end of the strike. Mining communities and their elders have a long historical recall that is specifically logged in the annals of the community memory, they rarely ever forget those who breach the tradition and culture of their communities, perhaps best captured by an incident described by Phillips, (2017) recalled by Ian Chalmers an ex-miner, while on Cowdenbeath High street one Saturday morning, he received a donation from an elderly gentleman, while on the opposite side of the road another elderly gentleman, witnessing the exchange, shouted, ‘Is that conscience money, ya bastard?’ The elderly gentleman then crossed the road to inform Ian that the man had been a scab in 1926. The social costs of strike-breaking were not temporary, but lifelong, with the loss of community, friendships, and identity.

Solidarity miners’ strike 1984-1985

The coal miners and their trade union the NUM and the National Union of Miners Scottish Area (NUMSA), managed to curate a solidarity among their members, that traversed class, occupation, and community. The solidarity between trade unions in the different sectors was limited, many members and leaders of other trade unions sympathised with their cause, however, were not prepared to join forces due to a multiplicity of factors. These factors included the controversy surrounding the NUM's initiation of clause 41 and the perceived anti-democratic nature in which the strike was called. Additionally, the legislation that was enacted by the Thatcher government had a chilling effect on trade union leadership. Furthermore, a rise in unemployment led to weakened trade union bargaining power and the fear of further job losses. In addition, the social security bill enacted in April 1980 meant that trade unions would have to finance strikers as the bill prevented strikers from claiming benefits. Moreover, the Employment Acts of 1980 and 1982 made it unlawful to engage in sympathetic strikes and made it possible for employers to sue trade unions for damages. In addition, both Acts made it illegal to peacefully picket alongside other unions, limiting the number of pickets. Trade unions immersed in this legislative environment, therefore, made it extremely difficult for trade union leaders to justify to their membership to come out in support of other trade unions, considering weighting the harm this may have incurred on trade unions and their priority, to do what is in the best interest of their membership. Further, difficulties were the recession and job losses, having a knock-on effect in other sectors with the concern that striking may lead to extra job losses. The miners were isolated and this was part of the strategy mentioned in the Ridley report that was made with this intention.

While the miners were isolated, their solidarity in Scotland was solid, their communities rallied in support as did many members of wider society. The Scottish press was supportive to some extent, unlike the media in England, helping to fortify miners' resolve and gaining traction and sympathy from the general public. This is evident in the many local area groups that were formed in communities and those that were external and not directly related to mining communities. In terms of social solidarity and assessing the criteria via Durkheim's definition social solidarity is summarized as a normal order of society as opposed to chaos and conflict, and alternately, deviating from that normalcy creates a social pathology. Therefore, deviating from a normalcy of high rates of employment can be said, in the case of Scotland during the period 1979-1990 for substantial subunits in Scottish society, to be one that manifested in multiple social pathologies. The processes of accelerated deindustrialisation and the Thatcher premiership brand of neoliberal policies, and the abandoning of the principles of a moral economy compass, directed state actions, and the following substantial macro structural change, leading to significant harm for many British communities, in particular Scottish communities across the central belt and the west of Scotland. Pathologies, that were realised as chronic conflict, mass unemployment, identity crisis, atomisation of communities, breakdown of work culture, negative health outcomes, rising substance abuse (alcohol and drug), rising divorce rates, rise in crime, and a perceived democratic deficit with political apathy in Scotland. Communities impacted by the rapid change in society experienced alienation in a subjective sense in that they were estranged, powerless, isolated and to some extent detached from wider society. However, within their community were solidaristic and supportive. Many communities in Scotland had their sense of permanence obliterated and destabilised, their cultural attachments, for example, in mining communities being attacked and made obsolete, their identities that were reliant on that permanence were fractured, and their collective consciousness that served as cohesive to wider society was illegitimised by the attack on their subcultures, which in turn are derivatives of the wider societal cultural of Scotland, leaving behind feelings of being jettisoned from the national consciousness, as many of the participants in Clarke (2021) related, expressing feelings that their town or village had been abandoned to the forces of nature by wider society.

Conclusion

In conclusion, the acceleration of the processes of deindustrialisation during the Thatcher premiership 1979-1990 was characterised by enormous economic change and was not equalised by factoring the social costs that would for the most part be felt by communities that relied on heavy industry. The tumultuous change in Britain was catalysed by the miners’ strike of 1984-1985. For some, the changes were beneficial, but not to the extent one could say, were worth decimating entire communities that are currently, forty years on, suffering from the toxic half-life of deindustrialisation and showing little sign of recovery. Although many would disagree and would forward a view that it was medicine that was needed, the medicine in this case caused psychological, physical, and social pathologies for individuals and communities, in a multifaceted social direction, for example in social inequality, physical and mental health and loss of identity. The political attack on trade unions was unprecedented by historical standards and in many ways revealed an infantile mindset within the Conservative party glazed over with the pretence of a higher economic purpose, that was in many cases within heavy industry unjustified. When the NCB was audited by academics, this was revealing as to the extent of either fraudulent or incompetent accounting. The Labour Party missed an opportunity in opposition to expose the false accounting practises of the NCB, which would have shown the viability of the coal industry and mitigated the social pathologies that were to follow and the civil liberty violations by the arbitrary development of police powers. The latter has in part been remedied by the Scottish parliamentary report on police behaviours during the strike, resulting in a variety of criminal convictions accumulated during the miners’ strike 1984-1985 being pardoned (Scottish Government, 2024). However, could go further by compensating those miners who were dismissed by the NCB. Scottish miners were arrested at double the rate of those in England and three times more likely to have been fired for striking by the NCB. Trade union bargaining power was effectively neutered, while employer power was enhanced creating a power asymmetry between worker and employer. Neoliberal policies ran through almost every institution in Britain creating inequalities on an industrial scale. The policing resources employed against the miners were inordinate and the largest ever seen in British history. In addition, the deployment by Thatcher of UK intelligence services against the NUM may be considered malign at best and criminal at the other end of the scale, by using the full might of the state with the aim of realising her ideological goals. Unfortunately, Britain was to endure an almost ideological fundamentalism by personalities who were at the helm of major institutions simultaneously, Margaret Thatcher in government and Arthur Scargill heading the National Union of Miners, that resulted in a battle of ideologies with mystifiers and inversions dominating, leading their actions. Perhaps if there had been a more levelheaded approach to deindustrialisation, with a vision for the future, in terms of employment earlier in the process, the eventual social upheaval and devastating impact on communities in the 1980s, may have been alleviated in a more dignified and fair manner. The larger and longer effects on Scottish society remain prominent in the memory of Scots, currently manifested in an unresolved political, cultural, and social tension, left in the wake of deindustrialisation, accompanied by the emasculating of trade unions and the attack on the welfare state. The former points to associations, that with the limited bargaining power of trade unions collective power was not as effective, and that the legislative environment meant that individuals for example during the miners’ strike 1984-1985, particularly in England, were more willing to meet the social costs of community rejection and individual action in place of collective action, for their individual gratification. In terms of deindustrialisation, privatisation, and deregulation it was clear that all the formers had a negative impact on large swaths of Scotland’s population and left an indelible mark in the minds of many Scots, significant in the sense of a perceived democratic deficit, and with some justification, that has continued into the contemporary period. Further research on the psychological and cultural impacts of this era may indicate that neoliberal policies alongside deindustrialisation are responsible for the contemporary crisis and massive increase in mental health issues in Scotland.

Bibliography

Abel‐Smith, B., (1992) The Beveridge Report: its origins and outcomes. International Social Security Review, 45(1‐2), pp.5-16.

Arnold, J., 2023. The British Miner in the Age of De-industrialization: A Political and Cultural History. Oxford University Press.

Bassot, B., (2022) Doing qualitative desk-based research: a practical guide to writing an excellent dissertation. Policy Press.

Beale, D., (2005) Shoulder to shoulder: An analysis of a miners' support group during the 1984-85 strike and the significance of social identity, geography and political leadership. Capital & Class, 29(3), pp.125-150.

Benassi, D., (2010) " Father of the Welfare State"? Beveridge and the Emergence of the Welfare State. Sociologica, 4(3), pp.0-0.

Black, W.K., (2014) Posing as hyper-rationality: OMB’s assault on effective regulation. New Economic Perspectives, 27, Available at: Madness Posing as Hyper-Rationality: OMB’s Assault on Effective Regulation | New Economic Perspectives [Accessed 9 November 2023].

Canmore, (2024) Material and moral resources: The miners strike 1984-5 in Scotland. Available at: The Miners' Strike in Scotland 1984-1985 | Canmore [Accessed 11 April 2024].

Cameron, E., (2012) 'The Stateless Nation and the British State since 1918'. in TM Devine & J Wormald (eds), The Oxford Handbook of Modern Scottish History Oxford: Oxford University Press 620-34.

Clark, A., (2022) Fighting Deindustrialisation: Scottish Women’s Factory Occupations, 1981-1982. Liverpool: Liverpool University Press.

Clark, A., (2023) ‘People just dae wit they can tae get by’: Exploring the half-life of deindustrialisation in a Scottish community. The Sociological Review, 71(2), pp.332-350.

Clarke, J., Gewirtz, S. and McLaughlin, E., (2000) Reinventing the welfare state. In Clarke, J., Gewirtz, S. and McLaughlin, E. (eds) New managerialism, new welfare, London: SAGE, pp.1-26.

Coderre-LaPalme, G., Greer, I. and Schulte, L., (2023) Welfare, work, and the conditions of social solidarity: British campaigns to defend healthcare and social security. Work, Employment and Society, 37(2), pp.352-372.

Collins, C. and McCartney, G., (2011) The impact of neoliberal “political attack” on health: the case of the “Scottish effect”. International Journal of Health Services, 41(3), pp.501-523.

Davidson, N., McCafferty, P. and Miller, D., (2010) Ch. 1 ‘What Was Neoliberalism?'. In Neoliberal Scotland: Class and Society in a Stateless Nation (pp. 1-89).

Daniels, G. and McIlroy, J. eds., (2009) Trade unions in a neoliberal world (Vol. 20).Routledge, Taylor & Francis, New York and London.

Dorey, P., (2014) The steppingstones programme: the conservative party’s struggle to develop a trade union policy, 1975–79. Historical Studies in Industrial Relations, 35(35), pp.89-116.

Dunne, B., Pettigrew, J., & Robinson, K., (2016) Using historical documentary methods to explore the history of occupational therapy. British Journal of Occupational Therapy, 79(6), 376-384.

Ewing, K.K., (2005) The Function of Trade Unions, Industrial Law Journal 34(1), pp. 1-34.

Farrall, S., Jennings, W., Gray, E. and Hay, C., (2017) Thatcherism, crime, and the legacy of the social and economic ‘storms’ of the 1980s. The Howard Journal of Crime and Justice, 56(2), pp.220-243.

Featherstone, D., (2021) From Out of Apathy to the post-political: The spatial politics of austerity, the geographies of politicisation and the trajectories of the Scottish left (s). Environment and Planning C: Politics and Space, 39(3), pp.469-490.

Flick, U., (2018) An introduction to qualitative research. Sage.

Gibbs, E., (2021) Coal country: The meaning and memory of deindustrialization in Postwar Scotland, London: University of London Press.

Glasgow Times, (2015) Miners Strike: 30 years on, memories still raw over bitter battle. Available at: Miners Strike: 30 years on, memories still raw over bitter battle | Glasgow Times [Accessed 9 March 2024].

Gofman, A., (2014) Durkheim’s theory of social solidarity and social rules, in Jeffries, V. (ed) The Palgrave handbook of altruism, morality, and social solidarity: Formulating a field of study, New York: Palgrave Macmillan, pp.45-69.

Gough, I., (1989) Welfare state. In Social Economics (pp. 276-281). London: Palgrave Macmillan UK.

Hartwich, L. and Becker, J.C., (2019) Exposure to neoliberalism increases resentment of the elite via feelings of anomie and negative psychological reactions. Journal of Social Issues, 75(1), pp.113-133.

Harvey, D., (2005) A brief history of neoliberalism. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Hughes, R.A., (2012) ‘Governing in hard times’: the Heath government and civil emergencies–the 1972 and the 1974 miners’ strikes (Doctoral dissertation, Queen Mary University of London).

Jenkins, S., (2006). Thatcher and sons: a revolution in three acts. Penguin UK.

Lawson, C., (2020) Making sense of the ruins: The historiography of deindustrialisation and its continued relevance in neoliberal times. History Compass, 18(8), p.e12619.

Leopold, J.W., (1989) Trade unions in Scotland: forward to the 1990s? Unit for the Study of Government in Scotland, University of Edinburgh.

Linkon, S. L., (2018). The half-life of deindustrialization: Working-class writing about economic restructuring. University of Michigan Press.

Laitinen, A. and Pessi, A.B., (2014) Solidarity: Theory and practice. An introduction. Solidarity: Theory and practice, pp.1-29.

Matthews, K. and Minford, P., 1987. Mrs Thatcher's economic policies 1979–1987. Economic Policy, 2(5), pp.57-101.

McCartney, G., Collins, C., Walsh, D. and Batty, G.D., (2012) Why the Scots die younger: synthesizing the evidence. Public health, 126(6), pp.459-470.

McCloskey, D., (1976) On Durkheim, anomie, and the modern crisis. American Journal of Sociology, 81(6), pp.1481-1488.

McIvor, A. (2019). Blighted Lives: Deindustrialisation, Health, and Well-being in the Clydeside Region. 20 & 21: Revued'histoire144.

McIvor, A., (2020) “Scrap-Heap Storiesˮ: Oral Narratives of Labour and Loss in Scottish Mining and Manufacturing. BIOS–Zeitschrift für Biographieforschung, Oral History und Lebensverlaufsanalysen, 31(2), pp.5-6.

Miller, D., (1995) On nationality. Oxford, Clarendon Press.

McCartney, G., Collins, C., Walsh, D. and Batty, G.D., (2012) Why the Scots die younger: synthesizing the evidence. Public health, 126(6), pp.459-470.

McCrone, D., (2020) 'Who do you say you are? The politics of national identity 'Who do you say you are? The politics of national identity | Centre on Constitutional Change.